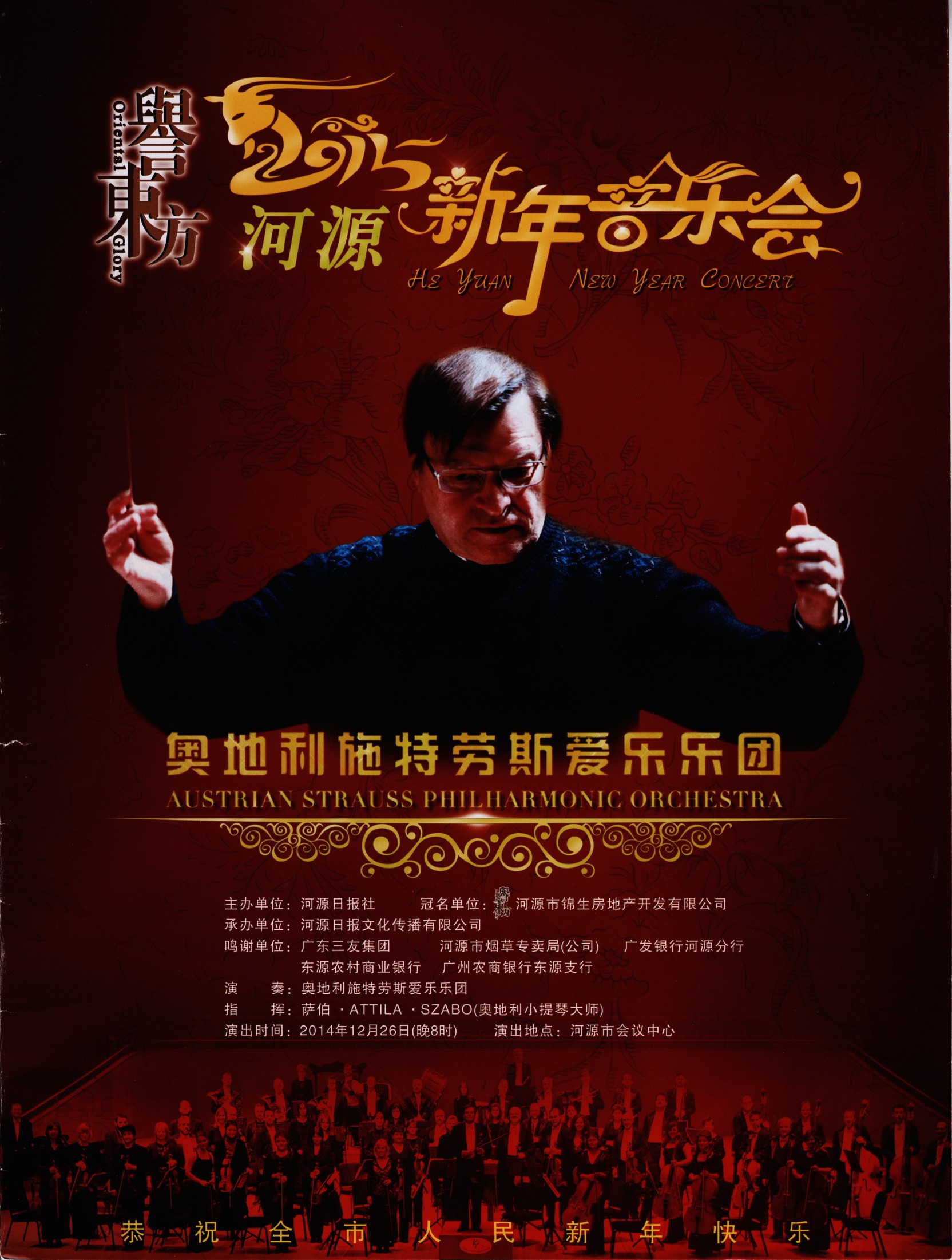

ATTILA SZABO VIOLINIST

Attila Szabo was born in Pestújhely in 1941. His brother is also a violinist, his sister an engineer. He inherited his love of music and his talent from his musical parents. He started playing the violin at the age of 9, and when he listened to his brother playing the violin with great success at college, he knew already then that music would be his life. His wife, Margit Basinszky, is also a violinist, with a family that goes back hundreds of years and which has produced musicians in every generation. His adult children are also involved in music. During his international career, he has created much more than music: he has also become a renowned and accomplished art collector. This website is a record of his work, and its content is constantly being expanded.

He studied the violin at the Budapest Conservatory with Margit Lanyi, who taught him the famous school of Karl Flesch. He studied composition with Istvan Szelenyi. In 1962 he graduated as a violin and solfege teacher at the Béla Bartók Academy of Music. In 1960 he won the first prize in the National Music Competition with violin duo and string quartet. In 1969 he became a member of the State Concert Orchestra under the direction of János Ferencsik. He continued his career with the orchestra of the Rijeka Opera House, followed by a twenty-year stint as first concertmaster in Klagenfurt. During his tenure as concertmaster in the 1970s, he helped an extraordinary number of musicians from Hungary and Transylvania to find work abroad, and many of them were also hosted in his house for long periods. During his travels in Transylvania, he also did a great deal for local Hungarian culture, supporting Transylvanian folk artists for decades. During his career as a concertmaster, he also expanded his repertoire as a soloist. During this time, he perfected his skills with four years of study at the Mozarteum in Salzburg with one of the most important musicians of the 20th century, the world-renowned violinist, chamber musician and conductor Sandor Vegh, who gave him a direct link to the modern violin technique represented by Ysaÿe-Szigeti, the Franco-Belgian violin school. The repertoire of the Szabo Quartet, which he and his wife founded 60 years ago, consists of more than 300 works, which they have performed with more than 70 renowned musicians more than 700 times in 15 countries, and have recorded for radio and TV. His work has been recognised by the Austrian State and Chinese universities. This website and the associated Youtube channel present selected recordings of his life’s work. During Attila Szabo’s time as a concertmaster in the 1970s, he helped many musicians from Hungary and Transylvania to find work abroad, and hosted many of them in his home for long periods. During his travels in Transylvania, he also did a great deal for local Hungarian culture, supporting Transylvanian folk artists for decades. Read more in this interview with him, conducted by Cafe Momus in August 2014.

Outstanding partnerships

Attila Szabo has enjoyed the company of artists such as Tamas Vasary, Adam Medveczky, Csaba Onczay, Livia Rev, Jörg Demus, Adam Fellegi, Lucia Megyesi Schwartz as a co-conductor at his solo concerts. The Szabo Quartet has given hundreds of concerts with 70 other outstanding artists from more than ten countries. As soloist and conductor he has been a regular guest of 7 ensembles:

- Göteborg Chamber Orchestra.

- Göteborg Chamber Orchestra, DODICI Chamber Orchestra

- Győr Philharmonic Orchestra

- Klagenfurt Landessymphony Orchestra

- Camerata Budapest

- Rijeka Symphony Orchestra

- Alpen-Adria Kammerphilharmonie, where he was also concertmaster

Recordings

1. Cremonese Instruments (2004, Sony): Live Concert from the Mozartsaal, Konzerthaus Klagenfurt. Mozart, W.A.: String quartet in C major, KV 645. Dvorak, A.: Cypresses. Performed by the Szabo Quartet.

2. Doppelkonzerte (1996, MKA): Mendelssohn, Kovach Mendelssohn B., F.:, Double concerto in D minor for violin, piano and string orchestra Kovách, A.: Double concerto for violin, piano and ono orchestra. Performed by concertmaster Attila Szabo, violin, and Elisabeth Schadler, piano, and the Dodici Chamber Orchestra, Győr.

3. Takacs, Jeno (Hungaroton, 2000). Camerata Budapest, Dodici Chamber Orchestra Győr. Conductor and violinist: Attila Szabo.

4. Jeno Akacs (2001, Fono Records): Chamber music works Performed by Attila Szabo, violin, Manfred Plessl, violin, Gyöngyi Kevehazi and Adám Fellegi, piano, Attila Szekely, cello. There are also numerous other privately released recordings, which will be available soon on the website.

The SZABO-Quartett

– 300 works in the repertoire and the Haydn marathon

Attila Szabo founded the Szabó Quartet in 1979, which is now an institution in the Austrian musical world. In addition to classical and romantic works, the ensemble’s vast repertoire includes works by contemporary composers, including several works dedicated to them. The quartet has been commissioned to give 15 successful premieres and has also made numerous radio recordings. (Recordings and live broadcasts on ORF, MR Hungarian Radio. Notable among these are the “Beethoven Cycle” (broadcast in its entirety by Austrian Radio), “Mozart Cycle” in the Mozart Year 1991 (43 works, Austrian Radio broadcast live the closing concert on the 200th anniversary of Mozart’s death). These performances were followed by further cycles: the ‘Abendländische-Kammermusik’, the ‘Jubilee Concerts’, the ‘Hommagen’, the ‘Castle Concerts’, which found a worthy venue in many castles, monasteries and abbeys in Carinthia. Inspired by the southern climate, the richness of music-making together at the meeting point of different nationalities and cultures has been a great success. The quartet has won great acclaim in Austria, Hungary, Germany, Sweden, Italy, Switzerland, England and China.

CarinthiArte and the Haydn Marathon

The friendly society of the Szabo Quartet, CarinthiArte, was founded by Attila Szabo in 1997 to support young musicians and to stimulate the musical life in Carinthia. He surprised their music lovers and listeners with a great anniversary present by presenting the 83 quartets of J. Haydn, the complete Haydn cycle. With this marathon concert series, the Szabo Quartet presented the birth of the quartet repertoire in its entirety. The equivalent of 18 full concert performances between May 28 and 31 2015 – and unprecedented feat of strength in music history, requiring some 25 hours – the quartet performed Haydn’s great work, The Last Seven Words of Jesus on the Cross (Op.51 1787), on four consecutive days, and the work is performed on the Palm Sunday of every year.

Career in Asia

Over the last 20 years, Attila Szabo has been in intensive contact with China and Japan. He has been a visiting professor of violin and chamber music at several major Chinese music universities. Until the pandemic, he taught for several weeks a year in Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Zhaoqing, Nanchang, and Tokyo. He was celebrated as a soloist and conductor by huge audiences on successful concert tours in major cities in China, where he performed with his own orchestra, the Austrian Legacy Philharmonic Orchestra, in Beijing, Shanghai, Fuzhou, Ningbo, Hangzhou, Chengdu, Wuhan, Wenzhou, etc.

Radio recordings – Concerts

Numerous radio recordings were made in Austria, Hungary, former Yugoslavia, Sweden, Slovakia, Slovenia, Germany, Italy, England, Switzerland, Spain, Luxembourg, China (from 1970 to the present day, several times a year for decades).ORF (Austrian Radio and Television) and MR Hungarian Radio have regularly made studio recordings and live broadcasts several times a year from 1970 onwards. The Szabó Quartet is also broadcast on Duna Television and the BBC. Some of these include:

- 7 May 1973 (ORF I.) Sonata Evening Musikverein Kärnten (Ysaÿe, E.: Solo Sonata No. 2, Weiner,L.: Sonata in F-sharp minor) Attila Szabo violin – Elfriede Hriwa piano

- 7 April 1975 (ORF I.) B. Bartók: 2nd Violin Concerto Musikverein Kärnten Great Concert Hall.

- 1978 from April 18 (May 2, May 9) (ORF.1) : Beethoven-Cycle (10 violin sonatas Musikverein Kärnten. Attila Szabó violin – Philip Saudek piano

- 13 October 1985 (ORF 1) Sunday matinee in the theatre hall of the Radio. Haydn: Sunrise, Beethoven quartet in C minor, Ernő Dohnányi: op.1.

- From 20 January to April 1986 (ORF 1.): Beethoven-Cyklus: All the String Quartets. Szabó Quartet.

- 1996 April 25 (ORF 1) B. Bartók: 2nd Violin Concerto. Musikverein Kärnten, Great Concert Hall. Attila Szabo violin – conducted by Tamas Koncz – Győr Philharmonic Orchestra.

- 6 October 1997 (BBC): Oxford Holywell Music Room . Szabo Quartet, Kentner, L.: string quartet. Leo Weiner: String Quartet No. 2, Schubert, F.: “Death and the Maiden” Szabo Quartet.

- 5 October 1997: (BBC. London, The Yehudi Menuhin School. Louis Kentner: String Quartet, Schubert Fr.: “Death and the Maiden”. Szabo Quartet.

- May 13, 1998 (MR) Studio 6 “Concert cycle from the music of our century” Durko Zso: String Quartet I; Iannis I: String Quartet I; Kiskamoni-Szalay M.: String Quartet 2 premiere; Kovach A.: Piano Quintet. Szabó Quartet, Nina Kovacic piano

- 12 June 2000 (MR): Hungarian Radio Marvanyterem. Schubert Fr. A major rondo. Attila Szabo violin – conducted by Adam Medveczky. Dodici Chamber Orchestra

- 27 February 2000 (MR) Budapest Music Academy. Strauss R.: Violin Sonata. Attila Szabo violin – Adam Fellegi piano

- 16 February 2005 (ORF) Klagenfurt, Musikverein Kärnten Concert Hall. Szabo-Quartet- Jörg Demus piano. Schumann R.: piano overture.

- 30 January 2000: (Duna Television) Klagenfurt Megyehaus Címerterme. Szabo-Quartett 20th Anniversary Concert W.A. Mozart; Konczei A.: String Quartet No. 1, Tchaikovsky P.I.: Florence Memories (string quartet). Szabo-Quartett: Attila Szabo 1st violin, Karnburger, Mária 2nd violin, Margit Szabo viola, Hajdany, Gertraud cello & Lehner, Wolfgang viola – Hajdany Jozsef cello.

Summer Carinthian masterclasses and education

Since 2004, until the pandemic, Attila Szabo summer courses in Ebenthal and Kötschach in Carinthia (“Europe-Asia string courses”, see www.music-master-class.com) have been repeated regularly. In order to prove their skills, the young musicians who took part were invited to concerts in Austria and Italy: In Klagenfurt, Perugia, Cremona, Venice, Enemonzo and Kötschach, the young musicians were greeted with warm applause by the audience. Music education is an important part of Attila Szabo’s life. In addition to his position as concertmaster in Klagenfurt, he was also a violin teacher at the Viktring Music High School for 30 years. Unforgettable are the chamber music performances and the concerts of the school orchestra, such as G.F. Haendel’s Water Music, J.S. Bach’s Brandenburgische Concerts, the Paukenschlag Symphony by J. Haydn and the many concertos performed by his students.

House music and the house concert hall

In 1982, the artist couple found a home in an old inn in Ebenthal, near Klagenfurt, where they held summer courses and regular house music in their concert halls. It was carefully renovated with a lot of work. With a capacity of 90 people and a collection of instruments, books and carpets, the attic concert hall is a frequent venue for local intellectuals, including Count Goess. With its warm, personal charm, the “Oremushaus” concert hall has become a favourite meeting place for chamber music enthusiasts and a centre for “CarinthiArte”.

Awards

In recognition of his work, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Province of Carinthia on 10 July 2001. For his musical achievements he was awarded the title of “Professor” by the Austrian President on 8 June 2010.

MY MEETING WITH SÁNDOR VÉGH

Two weeks before a very important concert of mine (Bartók’s Second Violin Concerto in Klagenfurt), I overheard that Sandor Vegh was teaching in Salzburg. I went to Salzburg the very next day. I found him in the Mozarteum’s special hall, crowded with students. As soon as I entered, he asked me as a stranger why I had come, was I looking for someone? “I would like to play for you, if you would allow me”. “Of course” he said, “just wait until the end of the lesson”. Later he listened to the end of Mozart’s Violin Concerto in A major from the beginning to the last note without a single word. As soon as I finished, he frowned, “man, where have you been?” I told him about my life so far (my studies, my previous jobs and that I have been the first concertmaster of the Klagenfurt Opera House for 5 years). When I asked him if I could study with him, he said that he did not take orchestral musicians on principle, that he demands a lot and that he is an egotist who wants his teaching to produce results, which requires the student to be free. “But” he continued “I’ll make an exception with you”. He also noted that it is a misconception to think that there are miracle professors. Not every professor is right for every student, which is also true the other way round, but there are, of course wonderful students. “When I come, I have to come to Salzburg for two or three days at a time, not just for one lesson, because I have to listen to other students’ lessons, because they have the same problems and I can benefit from that.”

And so began four and a half years of the most rewarding years of my studies, during which I was incredibly enriched by the gifts of learning. As soon as I asked him after my first lesson how much I owed him, he said “you can’t pay me that”. And it stayed that way for the rest of the years. Today, I can honestly only repay that gift with gratitude. I have been able to spend a lot of time with him beyond my teaching hours. Day after day, I was the guest of Sándor Végh and his wife from breakfast till dinner. I still remember every day his kind invitation to casually eat the delicacies he offered me: “Eat it with love, my dear”, because that’s what they used to say in their home in Transylvania, in Cluj!! After an early breakfast, he worked with me for an hour before we went to the Mozarteum, where he treated me as an exceptional student of the school. It was a very hard and demanding lesson – which was usual in the old Hungarian school. Sándor Végh always said that a talented person has to endure it – or, if it is too much, stop studying. After lunch, he took a short nap and then worked with me for another hour at home before we went to the afternoon classes at the Mozarteum, where he again worked with me. Those hours we spent together were of the utmost importance to me. Above all, the sparkling conversation between his wife Alice and him and the incredibly interesting stories took away a lot of my inhibitions. After such hours, I was literally full of new ideas and thoughts.

We had many points of contact. Beginning with Végh’s enormous knowledge of the language, we had a long chat about the Sumerian language, which was on my mind at the time. He was also interested in my documentaries about the former Hungarian culture in Transylvania. Both our roots come from Transylvania: He was born in Kolozsvár and I have many relatives in Transylvania through my grandmother. I have traveled extensively in this area and filmed local customs.

He was particularly impressed by the genuine folk art. He particularly liked the variety, the ability to vary, and the genuine feelings that are expressed in the art there. All of these artifacts, earthenware burnt and painted, wood carvings, or embroidery, were for him pieces of art, unique and not to be found elsewhere. Along this route is also an art that calls for utmost variability and richness in nuances. We also had a common interest in the beauty of musical instruments and cultivated the art of recognizing their origin, based on publications of the trade. Referring to his predilection for violin bows, he called himself a bow bigamist.

Over time, a deep, untroubled friendship developed between our families. We particularly remember the unforgettable summer invitations to Cervo by the sea in Italy. But we were just as happy when we were able to welcome the Végh family as our guests for several days in Ebenthal. It was nice to see how the calm atmosphere at our house had a beneficial effect on him when he wanted to rest after periods of hard work.

So we visited all the important sights of Carinthia and also some of neighboring Slovenia. He was particularly impressed by the beauty of the Carinthian landscape and the magic of nature.

During our tour of the lakes, Végh was also interested in Brahms in Leonstain and we also drove past Mahler’s house. We will always remember his cheerful nature, good humor, and laughter at jokes and witty stories.

Hardly a day has passed since I met him that I don’t think about his words. I could only play when I imagined I saw him in front of me and thought, how would he play, how would he sound?

It was immensely exciting to watch him play, whether in class or in concert. And often one felt that one had to spontaneously applaud his wonderful solutions. When he picked up his Stradivarius, he was transformed and changed, as if rays from heaven were shining on him. His suggestiveness was overwhelming, at times like the caress of a woman’s hand, at times like the crack of a whip.

Végh’s beautiful, soulful tone was always speaking, as if he wanted to talk about something. Végh also said that all Italian sonatas begin as if they were telling about times long past. But the constant intensification of his music gave the impression that everything was taking place right now.

Végh’s flawless, amazing technique was never L’art pour l’art; with him, Paganini also acquired a truly uncanny depth.

Again and again, we admired Végh’s incredible memory. No one could bring him anything that he would not have played immediately, regardless of whether it was an etude or a concert piece. For him, music was the measure of all things and we should always approach problems from the musical side.

In principle, technical solutions should serve the music – here he showed no mercy. It was also always important to look for the analogy in other pieces to determine how to solve this or that in another way.

Through his fundamental knowledge, Végh connected us to earlier times. Through him we became the late descendants of French violin playing (from Hubay via Vieuxstamps to Rode and Beriot) and through him we have been able to recognize an almost forgotten style of playing.

It is fair to say: “If Pablo Casals was the king of the bow with the cello, it was Sándor Végh on the violin”.

The magic of the beautiful tone has travelled on the path of our lives. Ever since we founded our quartet, we have been listening to the recordings of the Végh Quartet, while preparing for our concerts, with the greatest pleasure. This is how we have expanded our large repertoire of more than 350 works of music. (This includes the entire Beethoven cycle and the entire chamber music literature of Mozart, Schubert, Brahms, Haydn…) In various cycles, we have played the different music of various countries in the most beautiful palaces and castles in Carinthia and elsewhere in Austria. These concerts have often been televised by the ORF, the Austrian Television Corporation. We have been able to introduce ourselves in many countries, like Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Hungary…and in great cities, like London, Oxford, Budapest… We have always played with a great preference for Hungarian works (Bartók, Kodály, Weiner, Szalay, Kovács, Takács, Durkó, Kenntner…) Over time, we set up a small concert hall in our house, in which we have organized concerts on a regular basis.

The most beautiful concerts I recall have been the orchestra concerts: Bartók’s Second Violin concert, which I have played with various orchestras, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Bach concerts…and the numerous recordings on long-playing records: Mendelssohn double concert for the violin and piano, Jenö Takács‘s entire chamber music works.

Every year at Easter, we play the musical masterpiece, ‘‘The Seven Last Words of Christ“ by J. Haydn. Here it is noticeable that the beautiful tone also ‘‘speaks.“ During the piece I also see images, because Haydn composed musical pictures. The music sounds different when the big crowd shouts, and the sound is melodious when Jesus speaks.

We recorded this masterpiece in an Italian church, and I later added the images, which Haydn’s music inspired me to see. These loving or angry images, these often contradictory feelings, which we ourselves feel during our performance, lead us through the story-telling, talkative sound of our violins to a result that expresses the meaning of the presented works to our listeners.

In Klagenfurt, I have often met great musicians. One of my most interesting memories has been to meet Henrik Szeryng. After his concert, we had dinner together, and he also generously spent the following day with us. After we had admired each other’s Guarnieri violins, he spent half a day playing on my two violins, and so I was able to admire his magical violin-playing at first hand. One of my violins reminded him of the violin of Josef Szigeti, because he said, ‘‘These instruments are like twins.“ (It is interesting to note that Sándor Végh, who had owned a Guarnieri del Gesu violin before his Stradivari violin, had also remarked that ‚‘‘my instrument and this violin are similar, like two eggs.“ Szeryng also asked me to play the violin, because he wanted to see how I played it. At his departure, he expressed the desire to carry on playing music together when he was to come the following year. Unfortunately, this meeting no longer took place, because of his death.

What do I owe to Végh?

When Sándor Végh spoke about the relationship between teachers and their students, namely, that ‘‘there are no miracle professors, there are only wonderfully talented students,“ I think he was only half right. The young generation observes their masters with admiration and passionate enthusiasm. The professor, in turn, enjoys the performances of his students, who have developed wonderfully through his guidance. Examples of this are Vieuxstemps and Ysaÿe:

One day, the old Vieuxstemps was strolling through the streets of Liège when he heard the beautiful sounds of a violin coming from a cellar. Looking for the source of the sound, he found 9-year-old Ysaÿe and sent him to study with his assistant, Wieniawsky. Ysaÿe later talked about the admirable teaching process of the old master and his assistant and how grateful he was for these lessons. Later Ysaÿe followed in their footsteps as professor at the Bruxelles Conservatoire. He became the most influential Belgian violinist and closed the gap between the old masters and the wonderful violinists of the modern age: Joachim, Sarsate-Kreisler, Heifetz, Francescatti. Ysaÿe, like all the great violin virtuosos, not only taught students, but was also able to attain higher levels of music culture with his own compositions. Ysaÿe’s 6 solo sonatas followed, with their breakneck and most exciting demands on the beginning development of Bach’s partitas and sonatas. Ysaÿe had dedicated all 6 of his sonatas to another selected and wonderful violin virtuoso or other talented students. (Szigeti József, Jacques Thibaud, Georges Enesco, Fritz Kreisler, Mathieu Crickboom, Manuel Quiroga)

Végh made friends with Ysaÿe’s son and the son of Ysaÿe’s student Crickboom. They told him and showed him how Ysaÿe played his own sonatas!

Béla Bartók, the great Hungarian composer and pianist, also had a great influence on the art of playing the violin. The history of music is not only grateful for his violin concerts, (The first one he dedicated to Stefi Geyer; the second one to Zoltán Székely.) but also for other works, like the great, heavy, but beautiful solo sonata, commissioned by and dedicated to Jehudi Menuhin. There are also the 6 Bartók quartets, which were a further development of Beethoven’s c-minor quartet. Bartók was friends with the young Végh, whose great violin virtuosity and technical ability helped him to compose his last two quartets. (So it is understandable why the Végh Quartet shows such elementary forces when interpreting Bartók and why all works of Bartók, played by Végh, are so easily understood and personable!

What a joy it was for me that I was allowed to take on these works of Ysaÿe and Bartók as parts of the authentic process of Sándor Végh. It felt like runners passing the rod to each other in a relay race.

I will never forget the respect and love with which Bartók listened to my radio recordings of the II. Violin Concert, the solo sonata, the Contrasts, Bartók’s Sonata for the violin and piano, and the radio broadcasts of my Ysaÿe solo sonatas. At our last meeting, when saying goodbye, he embraced me and said, as if it were an obligatory request: ‘‘You should never abandon the works of Ysaÿe and Bartók.“

What I owe to Végh’s lessons:

Végh consciously wanted to lead me to the cradle. Now I understand why it was so important to study the Études of Rode to the level of a concert performance. All these études deal with specific problems of violin playing, through which one can uncover the secrets of violin playing.

While Végh taught the old masters authentically, he was able to bring to life the great figures of music history and awaken their style of playing, their story-telling tone, and their way of creating images. Végh got all this from Hubay. An example of this is the St. Petersburg performance of Tschaikovsky´s violin concert. Tschaikovsky conducted his work himself; Hubay was the soloist. (At that time, Auer considered this violin concert to be unplayable.) Végh showed with which fingering, bowing, and phrasing Hubay brought this work to life and how Hubay carried out Tschaikovsky´s instructions, concerning individual passages. From this, I had an idea of what an ideal performance in Tschaikovsky´s time was like, and so this masterpiece has become one of my favourite pieces.

It brings me great joy whenever I play so many masterpieces for my students and my dear audience. I can say in Ysaÿe´s words: “I am happiest when I play the violin; then I love the whole world and let my feelings and my heart speak.“

Prof. Mag. Attila Szabo